-

Issue 85

-

Editor's Note

-

POETRY

- Hussain Ahmed

- Benjamin Aleshire

- Diannely Antigua

- Amy Bagan

- Theresa Burns

- Robert Carr

- Chen Chen

- Brian Komei Dempster

- Ben Evans

- Ariel Francisco

- Jai Hamid Bashir

- John James

- Luke Johnson

- Matthew Lippman

- Amit Majmudar

- M.L. Martin

- Rose McLarney

- Meggie Monahan

- Stacey Park

- David Roderick

- Annie Schumacher

- Donna Spruijt-Metz

- Noah Stetzer

- Ryann Stevenson

- Svetlana Turetskaya

- Emily Van Kley

-

BOOK REVIEW

- Oliver Baez Bendorf reviews After Rubén

by Francisco Aragón - Deborah Hauser reviews Crack Open/Emergency

by Karen Poppy - David Rigsbee reviews In The Lateness Of The World

by Carolyn Forché

- Oliver Baez Bendorf reviews After Rubén

Issue > Book Review

David Rigsbee reviews In The Lateness Of The Worldby Carolyn Forché

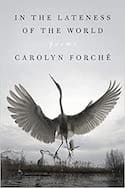

In The Lateness Of The World

by Carolyn Forché

by Carolyn Forché

96 pages

Penguin Press

Buy this book through our Amazon.com bookstore and support The Cortland Review.

Carolyn Forché's first collection in seventeen years, coming on the heels of her acclaimed memoir What You Have Heard Is True (2019), marks a kind of summit and summation of "the poetry of witness," Forché's term for a poetry that explores the relationship between the political and the personal. Is this another term for what might be called political poetry? This suspicion is based upon an unfounded fear that a poem must choose either aesthetic or ethical concerns. Forché's work takes its beauties seriously and is seriously beautiful not in spite of, but because of its deeper commitments to the value of individual human life.The humanitarian engine works at full throttle as it makes its way once again through devastations brought on by violence, exile, and upheavals historic, sexual, ethnic, and environmental. Thus her poems travel, to Vietnam, to El Salvador, to both modern and ancient Greece, to Eastern Europe, to Russia, and to the Middle East. Thus too she presents herself as a fellow-traveler, whose empathy appears not only in her life and choice of subject, but in the haptic grace of her craft.

For all the migration, the jostled masses at sea, the general movement and dislocation, often unwilled, from place to farther place that characterize the global sense of this collection, Forché opens with a meditation on stone, which by its very inertness would seem immutable to the pen. But stone's fate is presented as varied as those who encounter it:

collected from roadside, culvert, and viaduct,

battlefield, threshing floor, basilica, and abattoir—

stones, loosened by tanks in the street

from a city whose earliest map was drawn in ink on linen,

schoolyard stones in the hand of a corpse,

pebble from Baudelaire's oui,

stone of the mind within us

"Museum of Stones" (p. 3, ll. 2-8)

Note the tanks and the corpse's hand. You can't get very far with stone without meeting up with a blunt force even greater than the stone's obdurate indifference and very often, its heft. And yet the stone also, accommodating as well as defying our wishes, stands in contrast to our vulnerability (that corpse) and provides "cromlech and cairn (l.10)...stone from the tunnel lined with bones" (l. 14) with which to memorialize those who were briefly living, by lending a mute steadfastness, in spite of Ozymandias. Stones go to work supporting our need to elegize ("temples and tombs" [l. 12]), even as they are also, "paving stones from the hands of those who rose against the army/ stones where the bells had fallen, where the bridges were blown." (ll. 17-18) We are the figures to their ground, from pebble to mountain. That we live among stones allows us to consider them in a reflective sense, as in some ways a mirror, strange as it is to think. Now consider how the poem rises through its crescendo to find its still point:

All earth a quarry, all life a labor, stone-faced, stone-drunk

with hope that this assemblage of rubble, taken together, would become

a shrine or holy place, an ossuary, immovable and sacred

like the stone that marked the earth of the sun as it entered the human dawn. (p. 4, ll. 5-9)

David Attenborough couldn't have intoned a more fitting and dignified glimmer of the new. The dignity moves immediately to elegy, however, as we become familiar with the human end, as the "lateness" of the title suggests. In "The Boatman," we meet up with a kind of modern Charon, plying refugees:

We could still float, we said, from war to war.

What lay behind us but ruins of stone piled on ruins of stone? (p. 5, ll. 5-6)

Near the end of the poem, after uttering the dread names Aleppo and Raqqa and retrieving the eyeless corpse of a child pulled from the waves, he turns to his passenger: "You tell me you are a poet. If so, our destination is the same." (p. 6, l. 1) But the destination is often shifting, a mirage that beckons from "the hidden to the end of the visible," as she puts it in a moving elegy for poet Daniel Simko. ("Travel Papers," p. 26, l. 13) Here the boatman, who has no name but is more than a function, states the dilemma:

... Leave, yes, we'll obey the leaflets, but go where?

To the sea to be eaten, to the shores of Europe to be caged?

To camp misery and camp remain here. I ask you then, where? (p. 5, ll. 22-24)

It's a good question, whether you think of it as direct or rhetorical, but the point is that the poet and the boatman are companions in their uncertain journey. The mutuality doesn't end there. It's the boatman who speaks, but like a Rachel Whiteread sculpture, it is the poet whose presence frames his tale in the negative space of the poem, and in that sense, each bears the other across the dangerous water. Between floating corpses and plastic islands of environmental refuse, the sea itself turns noxious. In "Report from an Island," we find,

In the sea, they say, there is an island made of bottles and other trash.

Plastic bags become clouds and the air a place for opportunistic birds.

One and a half million plastic pounds makes heir way there every hour.

The pellets are eggs to the seabirds, and the bags, jellyfish to the turtle. (p. 9, ll. 11-12)

Nor was the sea at loss for danger before its present moment of degradation. It appears numerous times in In the Lateness of the World, as does water generally, present or drought, rolling seas or frozen rivers, drinking water, wells, buckets, cisterns. In "Fisherman," Forché appears with poet friend Ilya Kaminsky in St. Petersburg to visit a synagogue "as far back as a forgotten holiness," whose rabbi laments the scarcity of Jews ("There are only a hundred of us left in the city" [p. 17, ll. 12-13]), while outside,

... a fisherman waits on the river,

seated with a bucket beside him, his line in the hole, but in the last hour

water has surrounded his slab of ice, so unbeknownst

he is floating downstream, having caught nothing, cold and delirious

with winter thoughts, as they all are, and were, and as for rescue,

no one will come. (p. 17, ll. 13-18)

The sense is that the whole world, indeed, history itself, is beset with hazard and spotted with atrocity, much of it self-inflicted violence brought about by layers of historical predation indifferent to basic justice and fellow-feeling. Forché has famously put the fact before the public of poetry readers in "The Colonel," where a Salvadoran warlord dumps a grocery bag of human ears on the dinner table as the poet and her companion look speechlessly on ("My friend said to me with his eyes: say nothing."). The drum of intimidation has often sounded its beat in her poems, as if to ask: in caution, what response? And yet her answer is typically to offer a kind of strict testimony of images, as if she were organizing the holdings of a trial case, of which the dicta include the additional response of her readership (and reviews, such as this one), bringing the picture before a tribunal of peers, not just admirers. In other words, her poems are as much an ethical matter, as an aesthetic one. Which raises the post-Adorno question: how do we manage (again) the risk of aestheticizing violence? For example, "The Ghost of Heaven," we find,

The girl was found (don't say this)

with a man's severed head stuffed

into her where a child would have been.

No one knew who he man was.

Another of the dead.

So they had not, after all,

killed a pregnant girl. (p. 41, ll. 5-11)

Forché has written that giving form to the indignities that lie in wait when people are in extremis requires new forms that recognize and weigh the shattering experience of history in the transformation of form itself. It is a paradox, like any attempt to say the unsayable, including fragmentation and silence. It's no wonder that tragedy remains the most exalted ledge on the scala sanctorum of art. Her poems work by way of inlayed images, the call-and-response of impressions, frequently in motion, managing a dynamic that takes place between the known and the unknown, the piercingly personal and the urgently public, between the hardness of stone and the weightlessness of spirit, between earthly dawn and the grave. The late C. K. Williams was another master of this effect, including the political, and I suspect something of an influence. The hired car that glides past the hovels and debris on its way to the gated community is likely to contain them both. How we calculate complicity's role in the act of witness is the question her poems raise. How, after death, do we go back over the littered terrain? Well, one answer is elegy, supported by the forensic of images, a restorative labor that, among others, has Homer and Alice Oswald to recommend it.

Forché was raised a Roman Catholic. While I don't know the extent of her commitment to the faith of her upbringing, the residuals are clear here, as they are in the memoir, where nuns and priests work tirelessly, often at grave personal risk, on behalf of the oppressed and—it goes without saying—poor. There are other bearers of spiritual intent: Buddhas on the family mantle, the toe of one of the Bamian Buddhas pulverized by the Taliban, talk of the dead, as if they were alive, talk to the dead, journeys underground, tunnels, as if the "grotto of skeletons" ("Travel Papers," p. 28, l. 2) demanded access and egress. There are sadhus and Cistercians, assorted holy men "with their infinite paths to God." ("Transport," p. 68, l. 17). It's not surprising in this volume to find her speaking in terms of the "spirit." Nor is it just a metaphysical overlay. Along with the vanishings, mass killings, crossings, exiles, historical silences, and refugees we find ghosts and revenants, beings wanting back in, knowing oblivion served no justice, as if death itself must contrive to be alive. They certainly are in many of the poems. For example,

... death

it was, you said, but now nothing, the islands, places you have been, the sea, the uncertain,

full of ghosts calling out, lost as they are, no one you knew in your life, the moon above the whole of it... ("Toward the End," p. 70, ll. 5-8)

You feel the truth of that poem of Vallejo's where a lamented corpse relents at the gathering of the whole world and slowly raises up on its tired elbow. There is an old truism that a poem is either a hunting or a haunting. The poems here are haunted by the histories, personal and political. This feeling that the world, tragic as it is, is lit by some kind of exaltation, whether in fact or in expectation pervades the book. The feeling is captured in miniature in an image from "The End of Something":

This is the church of a thousand years: vineyards,

hummingbirds, swifts, chicory, swallows, bindweed,

and the ringing of bells for liturgy, births, an deaths,

with a flock of bells to tell the village of war or its end. (p.49, ll. 5-8)

Let me return with a brief look at "The Ghost of Heaven," a searching poem whose occasion is a journey to locate the body of a girl caught in the ruthless fighting in El Salvador in the 1970s. It's a poem that sums up much the tension and resolve that accompany What You Have Heard Is True. In the poem we encounter Leonel Gómez (nephew of poet Claribel Alegría), who first invited the poet to visit and document her findings and then advised her:

If they capture you, talk.

Talk. Please, yes.

You heard me the first time.

You will be asked who you are.

Eventually, we are all asked who we are.

All who come,

All who come into the world

All who come into the world are sent.

Open your curtain of spirit. (p. 41, ll. 14-16, p. 42, ll. 1-6)

This is a deeply felt and moving collection that, in the midst of its often violent and tragic occasions, raises poetry to that sustaining realm where art illuminates ultimate values and tells us both who we are, who we might have been, and who we still might be.